CARNIVAL KING OF EUROPE - Project objectives

INDEX GOAL 1 - museum research GOAL 2 GOAL 3 |

|

| providing, through: • museum research • direct fieldwork • cinematic documentation |

new grounds as towards some overall interpretative synthesis of European winter fertility rituals (i.e. “Carnivals”), in the context of the general framework of European culture history. In particular, the early, yet still unchallenged suggestions by Sir James Frazer (The Golden Bough, 1922, but also his own precious and largely unplundered commentary on Ovid’s Fasti, 1931) could be confronted and corroborated with more recent theories about the spread of agriculture in Europe along a SE/NW trajectory (cfr. Ammermann, A. J., Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. The Neolithic transition and the genetics of population in Europe, 1984; Renfrew, C. Archaeology and Language, 1987).

In this perspective, it can be possible to trace the progress of winter fertility rituals alongside the spread of the new agrarian ideology, as it can be inferred from its earliest Neolithic settings in SE Europe, through to its descent into the classical world, when we see these fertility rituals very much at the centre of the concern of specialized priestly sects (i.e. the Salii, the Arvales, etc.) within archaic Roman religious practice whence, alongside Roman conquest, the same ritual practices percolated again and spread throughout the two halves of the Empire.

|

|

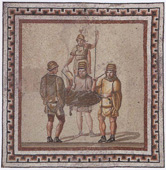

Roman Salii beating on a skin,

before a statue of Mars Mosaic, III c. AD. |

Later, in the middle-ages, in the townships of the West, winter masquerades tended to merge with the specific needs of the urban pageants, thus giving birth to the Carnival as we now know it (Nice, Viareggio, Venice, etc.), within the specific format of the burlesque cortege, that will be for present purposes left aside.

But in remote rural settings throughout Europe, the ancient masqued rituals remained unscathed and survived in the local folklore, where they continued to be celebrated to the present days in forms which are very much reminiscent of the ancient practice. In extreme synthesis, this is the historical frame of reference that will have to be tested, corroborated or discarded on the field within the context of “Carnival King of Europe”.

|

Kotilun gorria, |

Guirrio, Pola de Siera - Asturia (E) and Galitian mask (E) in Julio Caro Baroja, El carnaval, 1965 |

More specifically, some discussion about the constituent elements of the ritual, on the specific symbolic significance of the characters (i.e. goat-like “wild” figures vs. more hieratic silent masks wearing high cones, etc.), and actions (i.e.: ritual ploughing, mock marriage; bear chase; sentencing and execution of one pivotal figure, etc.) that are brought into play, as well as some notion about their diffusion across space and through time, will be brought forward.

|

Northumbria (UK), 1927 or 1928 photo by František Pospíšil |

• establishing a working network between some major European ethnographic Museums, with particular reference to the Alps and the Balkans, in order to exchange information and activities. This has been already attempted in the past (i.e. Project PEM – Partnership Ethnographic Museums), yet Carnival King of Europe puts before the attention of the institutions involved a common theme to work upon.

• contributing to a growing awareness as to the common cultural roots of all European peoples and/or nations, thus establishing some minor, yet not unimportant new landmark as to the making of a European identity.